AI readiness beyond the index

By

Nick Newsom

26 Jan 2026

|

Blog

The Government AI Readiness Index 2025 was recently released. Produced annually by Oxford Insights, it assesses government AI readiness across 69 indicators and 195 countries. I read it every year for the rankings, but also to see how others are framing what “readiness” means for the countries we work in and hope to support.

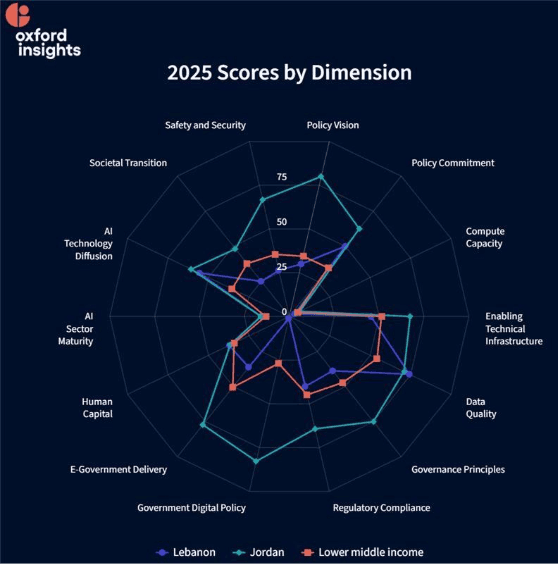

Jordan and Lebanon, our primary operational hubs, ranked 8th and 15th out of 20 countries in MENA, respectively, and 63rd and 117th worldwide. These numbers will likely be read closely by governments, donors, and reformers across the region.

Image: Performance of Lebanon, Jordan and lower-middle income country average in the Government AI Readiness Index 2025 (Oxford Insights)

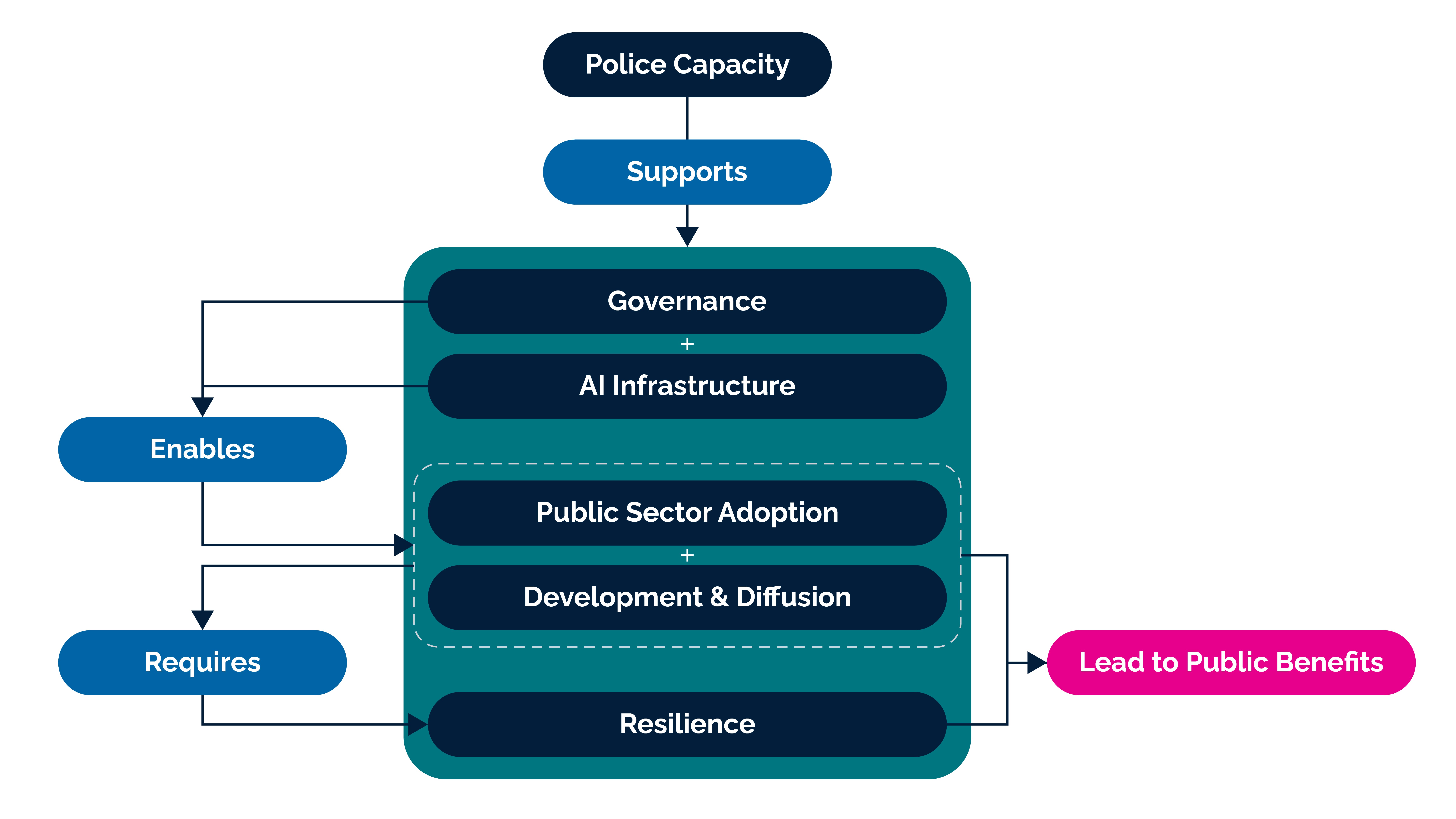

The Index is built around a clear theory of change: governments lead by setting policy, building governance frameworks, and investing in infrastructure, which in turn enables responsible public-sector AI adoption.

Image: “Theory of change relating government action on AI to public benefits from AI” (Oxford Insights)

This is an important piece of the puzzle, but it also reflects an ideal pathway that does not always capture how change unfolds in institutionally complex settings. In many such contexts, either policy capacity is weak, or policies exist but do not reliably translate into sustained institutional practice.

In practice, AI readiness is often built as much through delivery as it is declared through policy. And critically, a lot can still be done - even when governance is fragmented and infrastructure investment constrained. In many settings, institutions learn what to regulate, scale, and formalise by first seeing what works on the ground. Put otherwise, change is often delivery-led rather than policy-led.

Not every meaningful digital or AI-enabled intervention requires new legislation or a national strategy. Many high-impact improvements sit lower down the stack: centring users, fixing data, digitising workflows, and building tools that make services more responsive, accessible, and efficient. When these interventions deliver tangible results, they can generate the evidence and momentum needed to pull institutions forward.

In fragile or high-complexity settings where decision-making is often slow and consensus rare, private actors can play an important role in the core delivery model. Many governments lack the capacity to design, build, maintain, and adapt digital systems on their own. Even where political will exists, institutional constraints frequently make fully internal delivery unrealistic in the medium term.

In these contexts, the role of private actors is not simply to “deliver tech,” but to consciously align digital transformation with public interest objectives and global governance standards — even where local ones are weak, fragmented, or absent. In other words, not all private-sector involvement is equal.

That is where the real work sits: in baking governance directly into AI and digital programmes; in leading with value for users rather than with technology alone; and in embedding AI and data-driven tools within broader change programmes that build digital leadership and institutional capability over time. It also means helping government partners navigate local complexities that often act as practical blockers — for example, by designing systems that respect existing institutional realities rather than ignoring them, convening across conflicting and/or overlapping mandates, and testing approaches in ways that do not require immediate institutional commitment. This is often what prevents well-intentioned “best practice” models from collapsing when confronted with local political and institutional constraints.

Over the past year, Siren has applied this approach to help government partners use AI and data to:

strengthen environmental governance by monitoring illegal quarrying

clean and integrate fragmented social protection databases

improve responsiveness to public complaints during national elections

proactively manage misinformation and digital harms

There is a practical implication here for funders and reform partners. If one reads readiness frameworks too literally, the natural conclusion is often that the solution is to fund more policies, more strategies, and more governance frameworks.

These are all important, of course. But in contexts like Lebanon or Jordan, that is rarely where the primary bottleneck lies. In many cases, a far more catalytic investment is in agile, delivery-focused projects: initiatives that produce early results, can be iterated and scaled, and build momentum by visibly improving how institutions function. Models of readiness should therefore allow for feedback from delivery into policy, from pilots into standards, and from operational learning into governance.